HYDROLOGY

Thermal Plume Modeling Fundamentals: CFD Methodologies and CORMIX Regulatory Standards for 316(a) Variances

An authoritative guide to computational fluid dynamics (CFD) in hydrological contexts, comparing near-field jet dynamics (CORMIX) versus far-field hydrodynamic transport (DELFT3D) for regulatory compliance.

Discharging once-through cooling water requires more than just meeting a temperature limit at the "end of pipe." Under Section 316(a) of the Clean Water Act, dischargers must demonstrate that the thermal kill zone (mixing zone) does not cause "appreciable harm" to the Balanced Indigenous Community (BIC) of aquatic life. This demonstration relies entirely on Thermal Plume Modeling.

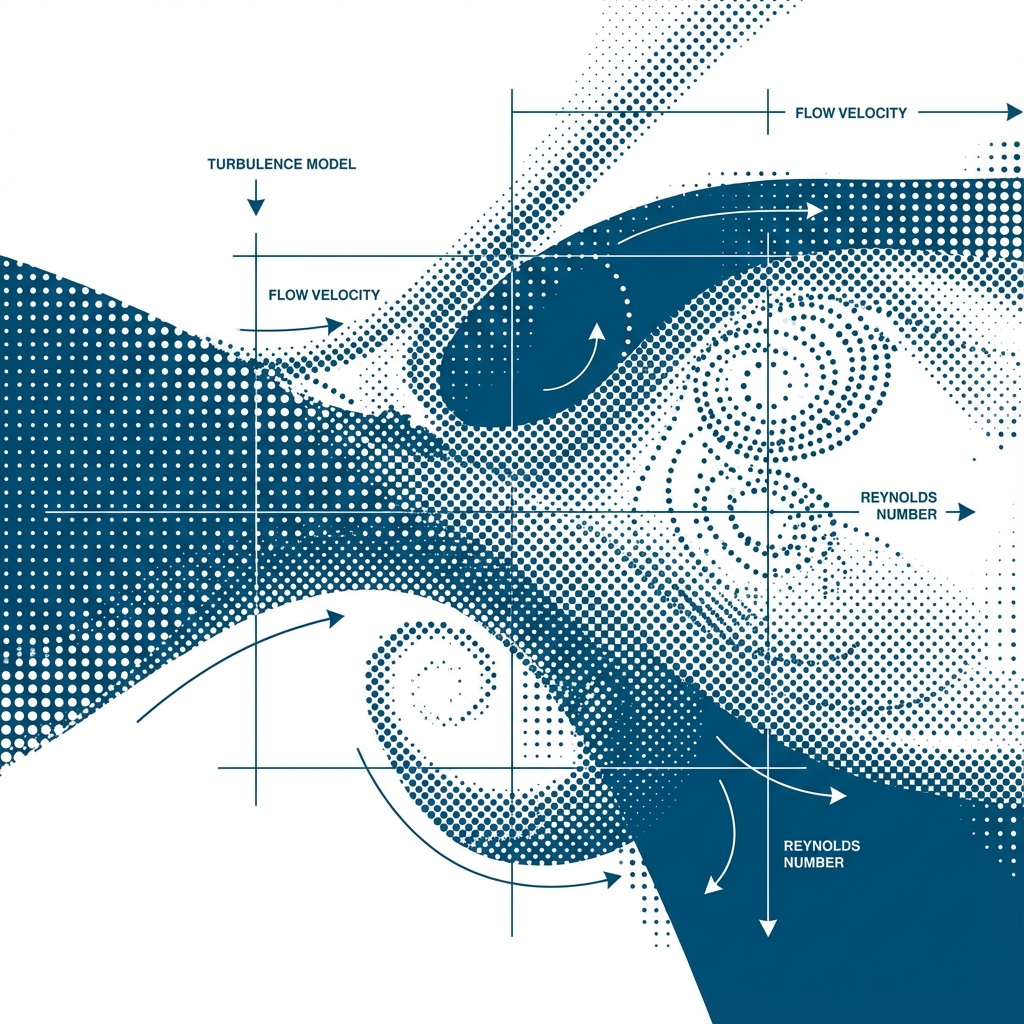

The Physics of Mixing: Near-Field vs. Far-Field

Thermal dispersion is governed by two distinct physical regimes. Understanding the boundary between them is critical for selecting the correct modeling tool.

1. Near-Field (Jet Dynamics)

In the immediate vicinity of the discharge port, the momentum of the effluent jet dominates. The sheer velocity of the water exiting the diffuser drives turbulent mixing, entraining ambient water. The governing physics here is momentum flux.

Standard Tool: CORMIX (Cornell Mixing Zone Expert System).

CORMIX is the gold standard for NPDES permitting. It uses length-scale classification to predict the trajectory and dilution of the jet. It answers the question: "How fast does the temperature drop within 100 meters?"

2. Far-Field (Ambient Transport)

Once the jet momentum dissipates, the plume becomes passive. It is now at the mercy of the river's ambient current, wind stress, and bathymetry. The governing physics shifts to advection-diffusion.

Standard Tools: DELFT3D, MIKE 21/3, HEC-RAS.

These are 3D hydrodynamic models that solve the Navier-Stokes equations over a grid. They are computationally expensive but necessary to show that heat doesn't accumulate in a bay or estuary over tidal cycles (thermal buildup).

Key Input Parameters: The Garbage-In/Garbage-Out Problem

Regulatory agencies (EPA, State DEQs) frequently reject models due to improper boundary condition selection. A robust 316(a) demonstration requires conservatism:

- Critical Low Flow (7Q10): You must model the river at its 7-day average low flow with a 10-year recurrence interval. This represents the worst-case scenario for dilution capacity.

- Maximum $Delta$T: The model must assume the plant is running at full load (maximum heat rejection) coincident with the hottest summer ambient water temperatures.

Diffuser Engineering and Optimization

If your baseline model shows a violation of the Mixing Zone standards (e.g., the 2°C isotherm extends more than 25% of the river width), the solution is engineering.

High-Velocity Multi-Port Diffusers: By replacing a single large open pipe with a manifold of smaller nozzles, we increase the discharge velocity (exit Froude number). This converts potential energy (head pressure) into kinetic energy (turbulence), dramatically accelerating near-field mixing.

We often use CFD to optimize the angle of these ports (vertical vs. downstream). A typical recommendation is a 20° vertical angle to promote buoyant lift while minimizing bottom scour, combined with a T-head alignment to maximize cross-flow interception.

Conclusion

Thermal plume modeling is not just a permitting exercise; it is an iterative design tool. A properly calibrated CORMIX model can save millions in cooling tower retrofits by proving that an optimized submerged diffuser meets biological criteria.

About the Author

Zayd Walid

Principal Consultant